AI Overlords Are Engineering a Broke Society ft. Ed Zitron

Extended Interview: Jeff Tweedy

In this web exclusive, Jeff Tweedy, front man of the rock group Wilco, talks with correspondent Anthony Mason about his solo project, a triple album called "Twilight Override."

Bruce Springsteen - Streets Of Minneapolis (Official Audio)

Bruce Springstein wrote & recorded a song about Minnesota’s battle against tyranny: Streets Of Minneapolis. “Our city’s heart and soul persists / Through broken glass and bloody tears / On the streets of Minneapolis.”

The Thousand Faces of Cassian Andor

“Hollywood script doctor Tony Gilroy had finally decided to write his friend Kathleen Kennedy, the president of Lucasfilm, a long-overdue letter; one that took the experiment that he, Gareth Edwards, and the cast and crew of Rogue One had started years ago to the next level. A radical pitch that framed the Star Wars Galaxy as the backdrop for a story about a revolutionary in-the-making, set upon a collision-course with history, destiny, and the unrelenting forces of Imperial oppression.”

1970 - Berkeley Protest Poster

The making of Z by My Morning Jacket - featuring Jim James

Really interesting interview that made me go back and give this one a deeper listen.

“For the 20th anniversary of the fourth My Morning Jacket album, we take a detailed look at how it was made. The band originally formed in 1998 in Louisville, Kentucky by Jim James, Johnny Quaid, Tom Blankenship and J. Glenn. After signing with Darla Records, they released their debut album, The Tennessee Fire in 1999. Danny Cash joined on keyboards before the release of their second album, At Dawn, in 2001. Patrick Hallahan took over on drums as they signed to ATO Records. Their third album, It Still Moves, was released in 2003. At this point, Johnny Quaid and Danny Cash decided to leave the band so they held auditions and recruited Bo Koster and Carl Broemel. For their fourth album, they hired producer John Leckie and began recording outside of their home studio for the first time. Z was eventually released in 2005.”

Cory Doctorow on Enshitification, The AI Bubble, Reverse Centaurs, and The Post-American Internet

The interviewer is downright useless here, but Mr. Doctorow seems to be able to keep him on track pretty well. Lots of good insights into our current shitty tech climate.

Music Fridays: McLean Bros. TRIO

Hoo boy, this smokes. Hopefully it winds up on Bandcamp soon.

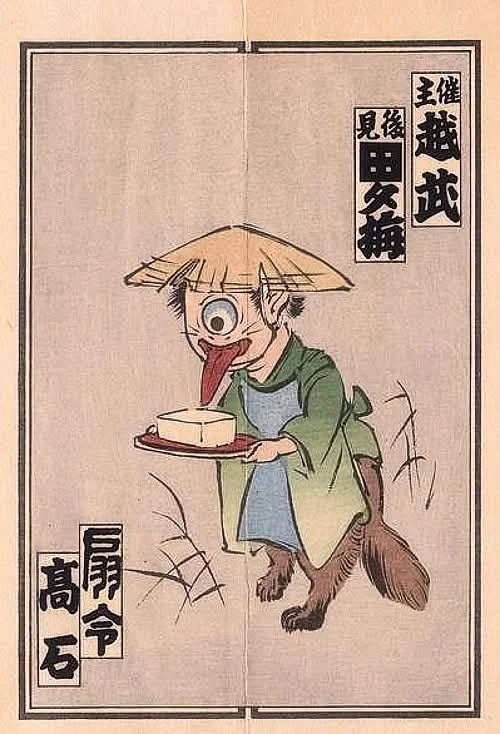

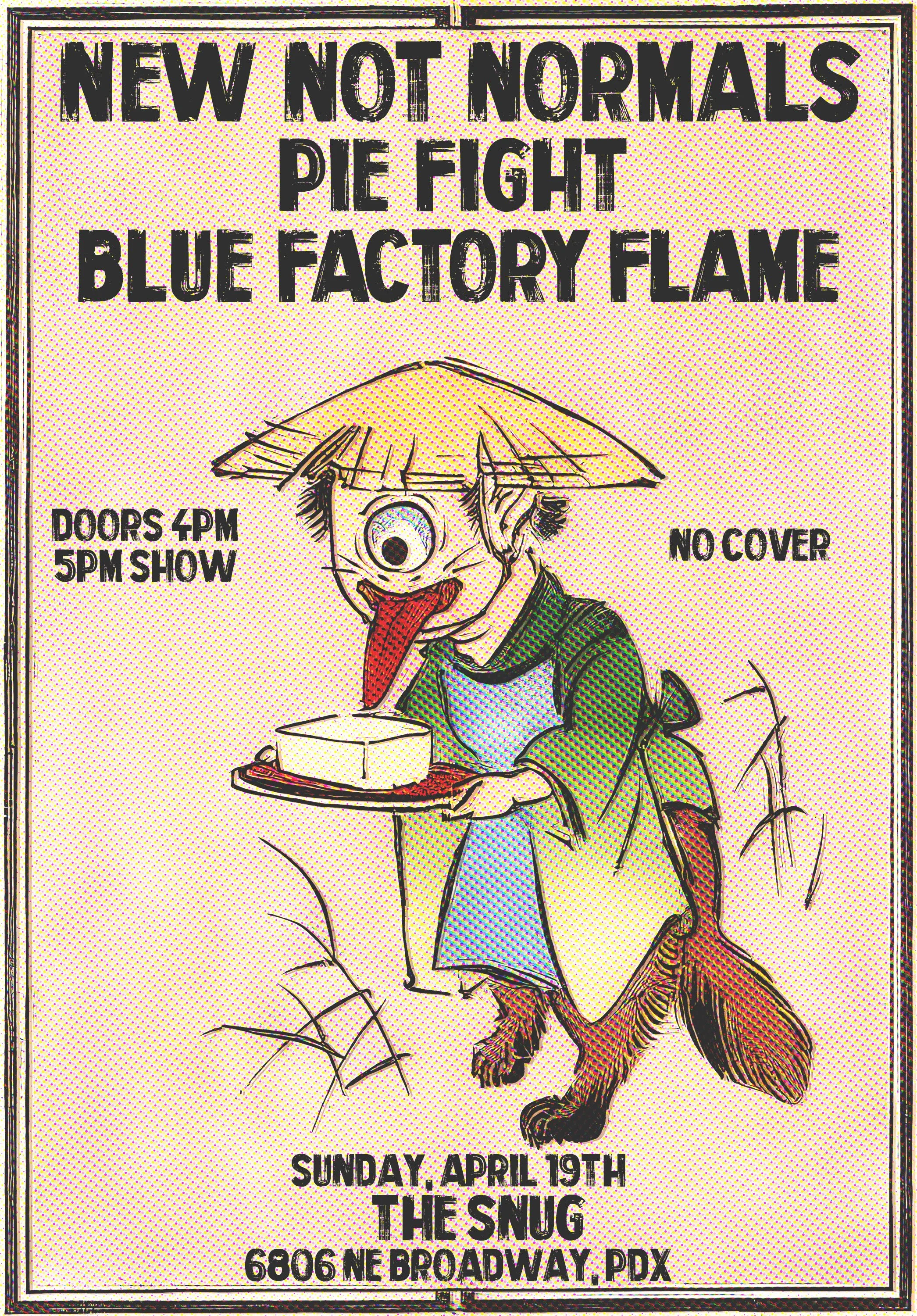

Poster adaptation: “Tōfu-kozō (tofu boy)” yōkai

Found this cool little dude looking up old wood prints and figured I’d spin out a band poster from it. It’s a “Tōfu-kozō (tofu boy)” yōkai which could easily be a skateboard graphic from the 80s. Super fun.

They are generally depicted wearing bamboo and kasa on their heads, and possessing a round tray with a momiji-dōfu on it (a tōfu with a momiji (autumn leaf) shape pressed into it[6]). The patterns on the clothing they wear, for the sake of warding off smallpox, include lucky charms such as harukoma (春駒), daruma dolls, horned owls, swinging drums, and red fish, and sometimes lattice patterns of the child that shows its status as a child can also be seen.”

"What is the point in making art when AI exists?"

“You know, you could do so many things like build a fence or spray some bleach on a cyber truck or any number of other more useful things, but instead you chose poorly and became an artist.”

How do we navigate our derangement of scale?

“The confusion may come from what the writer Timothy Clark calls “derangements of scale.” Our experiences as modern global humans, Clark writes, are like being “lost in a small town” and then handed a map of the entire earth for locating yourself and finding your way. In the Anthropocene, he writes, “we have a map, [and] its scale includes the whole earth, but when it comes to relating the threat to daily questions of politics, ethics, or specific interpretations of history, culture, literature, etc., the map is often almost mockingly useless.” Our scales are too imbalanced; we are unable to think the unthinkable. It goes without saying that it can be paralyzing, demoralizing, to be an individual acting as part of the collective, globe-sized world.” - by B. R. Cohen

We are living in a time of polycrisis. If you feel trapped – you’re not alone

“We are living in a time of polycrisis. If you feel trapped – you’re not alone

I hadn’t fully grasped how the idea of a better future sustained me – now I, like many others, find it difficult to be productive.

...

“What feels very different in the present moment,” Hershfield said, “is that it feels like it’s coming from multiple fronts. It’s everything from political uncertainty in the US and elsewhere, health insecurity from the very fresh memory of a global pandemic, job insecurity from AI, geopolitical insecurity, to environmental insecurity.”

All these crises are happening contemporaneously, and because they interact with each other, their effects pile up. Social scientists refer to these stacked crises as a polycrisis. During a polycrisis, radical uncertainty becomes rife.

The lack of predictability creates more doubt about the future, which blocks our ability to imagine ourselves in it.” - by Theresa MacPhail

Music Fridays: Khruangbin!

Khruangbin brought hypnotic “ii” reimaginings to KCRW’s Annenberg Performance Studio, weaving melodic bass, shimmering guitar, and deep-pocket drumming into an intimate, transportive flow. Posted Jan 12, 2026

Turn off all AI in Firefox.

Quick way to turn off all AI in Firefox to stop it from running so slow.

Type “about:config” in the address bar and click OK when it warns you that you can break stuff.

Next enter each one of these lines into the search bar and click the button to toggle them to “FALSE”. That turns them off.

browser.ml.chat.enabled

browser.ml.enable

browser.ml.linkPreview.enabled

browser.ml.pageAssist.enabled

browser.ml.smartAssist.enabled

extensions.ml.enabled

browser.tabs.groups.smart.enabled

browser.search.visualSearch.featureGate

browser.urlbar.quicksuggest.mlEnabled

pdfjs.enableAltText

places.semanticHistory.featureGate

sidebar.revamp

And that should turn it all off.

More on Bandcamp

I have been a big fan of Bandcamp for years now. I love that I buy my music and most the money goes to the artist direct. I was worried when they were bought out, but it seems like they are staying true to goal of “artists first”. And now they have banned AI from Bandcamp as well which is freaking awesome.

Keeping Bandcamp Human

“Today we are fortifying our mission by articulating our policy on generative AI, so that musicians can keep making music, and so that fans have confidence that the music they find on Bandcamp was created by humans.

Our guidelines for generative AI in music and audio are as follows:

Music and audio that is generated wholly or in substantial part by AI is not permitted on Bandcamp.

Any use of AI tools to impersonate other artists or styles is strictly prohibited in accordance with our existing policies prohibiting impersonation and intellectual property infringement.

If you encounter music or audio that appears to be made entirely or with heavy reliance on generative AI, please use our reporting tools to flag the content for review by our team. We reserve the right to remove any music on suspicion of being AI-generated.

With this policy, we’re putting human creativity first, and we will be sure to communicate any updates to the policy as the rapidly changing generative AI space develops. Thank you.”

This comment from Hacker News I think sums up AI art pretty well.

“Whenever I see defences of AI "art" people very often reduce the arguments to these analogies of using tools, but it's ineffective. Whether you use MS Paint, Photoshop, pencil, watercolor etc. That all requires skill, practice, and is this great intersection of intent and ability. It's authentic. Generating media with AI requires no skill, no intent, and very minimal labor. It is an approximation of the words you typed in and reduces you to a commissioner. You created nothing. You commissioned a work from a machine and are claiming creative authorship.” - frakt0x90